Why We Eat Black-Eyed Peas and Collard Greens on New Year’s Day

The Black American and Southern tradition is meant to bring good luck.

San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst Newspapers via Getty Images

Every New Year’s Eve, I remember my dad soaking a bag of dried black-eyed peas in a big bowl of water overnight, prepping them for the following day and tossing any with imperfections. In the morning, he would cook them down with ham hocks (pig knuckles) and other seasonings, and when they were done, scoop them over rice and eat them alongside collard greens and a slice of fresh skillet cornbread. Often referred to as hoppin’ john, black-eyed peas and collard greens are commonly eaten as part of a Southern tradition to bring forth good luck and prosperity in the new year.

As a kid, I wasn’t really a fan, especially not with their little eyes staring back at me. Maybe I’d have a spoonful in the hopes that that one bite would offer some good luck. But as I’ve gotten older and my palate has changed, it only feels right to take part in the ritual and enjoy a bowl with the rest of my family.

Having grown up in Jacksonville, Florida, my dad’s been eating black-eyed peas all his life. “That was a typical Sunday dinner. It was just a part of our diet,” he says. My grandparents were Depression Era babies, and it was an easy meal to make to stretch your dollar. “It was a cheap food source, but it was nutritional because with the rice, it provided a semi-complete protein.”

Through my grandmother and other family members, he was taught the significance of the dish later on. “I really didn’t learn about the New Year's Eve tradition until I was in my teens or 20s. [Based on what] I heard from relatives and reading about it, black-eyed peas are for good luck, and collard greens are for money.”

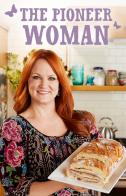

Matt Armendariz

Get the Recipe: Collard Greens

According to historian and food scholar, Adrian Miller, black-eyed peas represent coins, collard greens represent paper money and cornbread represents gold. Some say you’ll have the best chance at luck if you eat exactly 365 black-eyed peas, one for each day of the year. Others will even add a coin to the pot that the peas cook in, and it is said that whoever gets the coin in their dish will have the most luck in the coming year.

But where did the practice originate? While there are varying origin stories, both have ties to African American history and culture. One version says that during the Civil War, Union army soldiers in General Sherman’s troop raided the Confederate army’s food stash but left behind black-eyed peas, viewing them as a food for livestock. When the Confederate army had to make do with what remained, they were lucky to have the black-eyed peas to eat during the harsh winter, thus it became a symbol of luck and abundance.

Others argue it originated with enslaved people who ate black-eyed peas in celebration on January 1, 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation that abolished slavery was passed.

Indeed, historically, black-eyed peas were seen as a throwaway food for enslaved people and livestock. The crop was brought by enslaved Africans in the 1600s as they were transported to the Americas. West Africans have long considered black-eyed peas a good luck charm that warded off evil spirits, and they are often served on holidays and birthdays.

My dad echoes, “Once we got here, and we were enslaved, that was just part of the food source they would give us. They gave us anything that they really didn’t want.”

In the same vein, this is where the addition of ham hocks and other off cuts of meat used for flavoring began. “Oh, we got the scraps. That’s why we eat ham hocks, pig feet, neck bones.”

Regardless, ham hocks are crucial to the flavor of both black-eyed peas and collard greens. “The first thing you do is boil your ham hocks so the meat cooks and becomes tender. Then you put your peas in that water and add your seasonings, onions, salt and pepper, a little cayenne, stuff like that.”

There are many different ways to make black-eyed peas, but my dad and grandma swear by soaking them overnight for the best texture and bite. They are a labor of love, so patience is key. “Some people cook them right out the bag, however, they become mushy. They don’t have the textured body that you get when you soak them,” he says.

So this January 1st, just like many other Southern and Black families, we will have a bowl of black-eyed peas, collard greens and cornbread to start the new year off right. As my dad says, “Tradition and culture. It’s who we are.”

Related Content: